Strong International Education Rebound in 2021–2022

In 2021, the Canadian government processed more than 550,000 new student visa2 applications,

easily surpassing the record 425,000 processed in 2019.3 2022 is primed to smash 2021’s numbers,

with more than 450,000 applications already processed through the end of August.4

The United Kingdom has seen a similar boom. Nearly 450,000 students applied for a sponsored study

visa in 2021, up from 290,000 in 2019. And another 140,000 applications were submitted in the

first half of 2022, 80% more than in the same period last year.5

On the Uniwolc Platform, there was a 250% rise in UK applications

submitted between January and September 2022 compared to the same period in 2021.

Australia’s borders remained closed to international travel until mid-December 2021. Though there

were concerns its international education sector would be slow to recover, early signs are

positive. More than 213,000 Australian student visa applications were lodged from January to

August 2022, almost 25% more than the same period in 2019.6

If there’s a laggard among the top English-language destination markets, it’s the United States.

The US government processed just under 450,000 student visa applications for its 2021 fiscal

year,7 below the nearly 490,000 processed in fiscal year 2019. But 2022 may be more promising.

At Uniwolc, US applications spiked by 200% from January to September 2022 compared to the same

period last year.

Processing Delays Leave Students in Limbo

So many students vying to study abroad has put strain on the international education ecosystem.

Governments have struggled to manage the influx of applications, leading to processing delays

that have kept students in limbo for months and, in some cases, forced them to defer their

studies.

Canada’s total visa backlog reached 2.1 million in June, due in part to the Canadian government’s

efforts to relocate refugees from the Ukrainian crisis.8 Amid this backlog, average student visa

processing times hovered between 11 and 13 weeks throughout 2022 after falling as low as seven

weeks in 2021.9 And for certain countries, processing times have been much higher. For example,

processing times for Sri Lankan students reached 26 weeks in September.

In the US, estimated wait times for a student visa interview appointment climbed steadily over

the course of the year before falling sharply in September. But like Canada, significant

outliers remain. Remarkably, wait times of over a year remained for select Indian cities in

October. The US government authorized consular officers to waive the in-person requirement for

category F visa applicants through the end of 2022, but applicants must meet specific criteria

to qualify for a waiver.10

Facing its own visa processing delays, the UK government pointed to its own efforts to support

Ukrainian refugees as contributing to the backlog.11 In June, the British High Commissioner to

Nigeria implored applicants to apply for their study visa well ahead of when they might have in

previous years.12 In August, the government restored certain priority visa services, suspended

without warning in March, allowing students to pay a premium for faster visa turnaround times.13

By October, average processing times for UK study visas sat at

three weeks—significantly less than those for the other major English-language

markets.

Australia Faced Backlogs Of Five To Nine Months While Its Borders Were Closed.14 However,

The Australian Government Has Made Significant Investments To Expedite Visa Processing,

Adding 140 New Staff In May.15 Currently, The Government Advises Students To Lodge Their

Applications At Least Six To Eight Weeks Before Course Commencement.

The Australian government’s willingness to invest in better visa processing is an encouraging

sign for the sector. While the post-COVID boom will not last indefinitely, the ability to

deliver shorter visa processing times—as we’re currently seeing from the UK—is likely to be a

key point of competitive differentiation across markets moving forward. International students

are eager to begin their education abroad as soon as possible, particularly those who put their

plans on hold during the pandemic.

Student Visa Approval Rates a Key Differentiator

For some international applicants, the long wait for visa processing ends in disappointment. This

is less of a concern in the UK and Australia, where candidates less likely to secure a visa are

typically triaged out at the institution stage, and government approval rates are upwards of

90%.

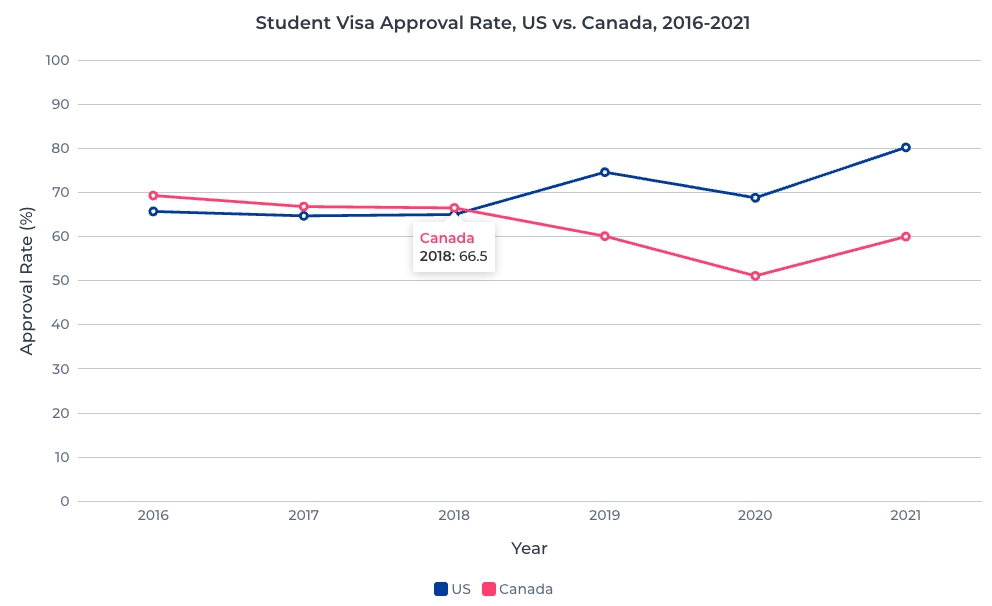

For Canada and the US, however, significant numbers of students are refused a student visa. From

2016 to 2018, approval rates for Canadian and US students visas were roughly on par, hovering in

the mid to high 60s. But since 2019, US approval rates have been consistently higher than

Canadian rates. In 2021, the US F-1 student visa approval rate hit 80%, its highest since 2013.

Canadian students, meanwhile, had just a 60% approval rate in 2021, and that rate fell to 57%

over the first six months of 2022.

Students have taken notice of these challenges. In the October edition of Uniwolc Pulse Survey,

66% of recruitment professionals surveyed said that visa processing times and approval rates

were a top concern for their students. US institutions would be well served to highlight this

advantage over their counterparts in Canada as they continue to rebuild their international

enrollment post-pandemic.

Affordability, Post-Graduate Work Top Concerns Among Students

A global recession looms over many economic projections for 2023. In October, the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) revised its global growth forecast for next year to 2.7%, down 0.2

percentage points from its summer projection.16 The 2023 forecast is the weakest growth profile

since 2001 except for the global financial crisis and the acute phase of the COVID-19

pandemic—arguably the two largest periods of financial uncertainty within the past 20 years.17

A new study from the World Bank Group also suggests that the global economy is edging toward a

recession in 2023, and that a string of financial crises could create lasting damage to key

markets.18

“Global growth is slowing sharply, with further slowing likely as

more countries fall into recession. My deep concern is that these trends will persist, with

long-lasting consequences that are devastating for people in emerging markets and developing

economies.”

— David Malpass, President, World Bank Group

Affordability Concerns Paramount with Recession Looming

Against this global economic backdrop, Uniwolc Pulse Survey asked counsellors what aspects of

studying abroad their students were most concerned about when choosing where to study.

Affordability issues dominated the results. More than 85% of respondents cited cost of studying

as a concern for their students. This was the most commonly occurring concern, followed by

post-graduation work opportunities (80%) and cost of living (73%). These results are

unsurprising, as high inflation and rising interest rates have dominated financial news around

the world throughout 2022.

Surveys of prospective international students have produced similar results. Across four of five

priority markets for US institutions, students indicated that cost of living was their number

one concern about studying abroad.19 Similar results held for the UK20 and Canada.21 For

Australia and New Zealand, four out of the top five worries students expressed about studying in

a different country are related to affordability. Cost of living (74%) was number one, followed

by availability of scholarships (65%), safety (55%), getting a job (49%), and finding

accommodations (49%).22

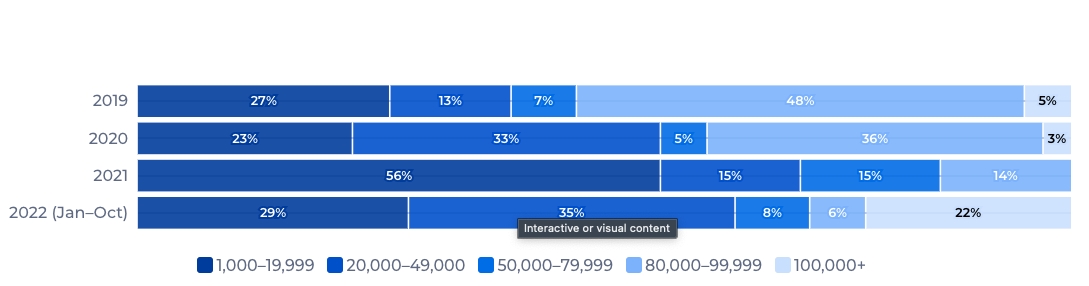

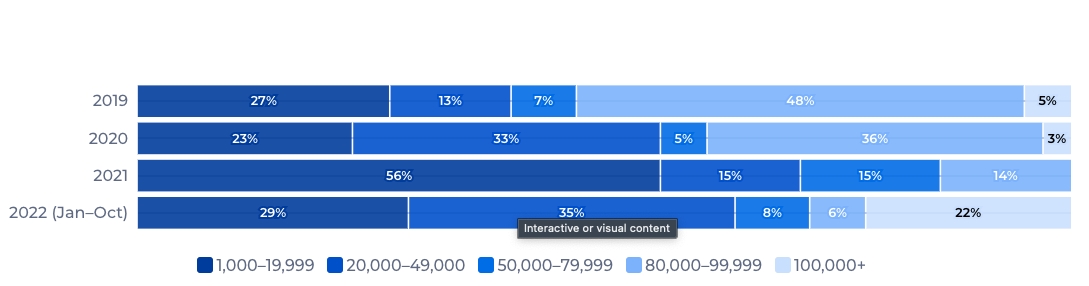

Uniwolc exclusive internal data also reflects the concerns students have about the affordability

of studying abroad. In 2019, 60% of searches on the Uniwolc Platform were for programs with

tuition fees of over 50,000 per year.23 But by 2021, this fell to 29%. Student willingness to

spend is up slightly in 2022. Even so, two out of every three students on our platform searched

for tuition fees below 50,000 per year. In short, even as students are once again on the move in

large numbers, they remain less willing (or able) to pay high tuition fees today than they did

before the onset of the pandemic.

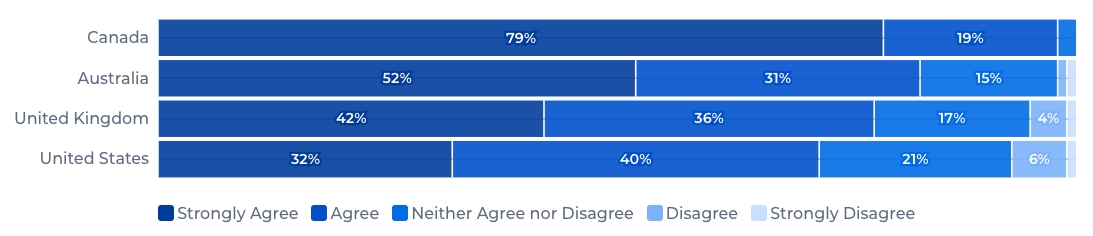

How do these widespread concerns about affordability affect destination market competitiveness?

Uniwolc Pulse Survey asked counsellors which major English-language destination markets were

more attractive from an affordability standpoint. Canada was the clear winner, with 87% of

respondents saying they felt that studying and living in the country was affordable for

international students. Canadian institutions should consider highlighting this

advantage—particularly those located in more affordable regions of Canada, such as the Prairies

and Atlantic provinces.

Strength of American Dollar Will Impact Affordability

Another macroeconomic trend impacting the international education ecosystem? The soaring value of

the American dollar. Shockingly, the euro fell below parity with the USD in August.24 The US

Dollar Index—which measures the value of the dollar relative to six other major foreign

currencies—reached highs in 2022 not seen since the turn of the century. While a strong US

dollar is good news for traveling Americans and students already living and working stateside,

it also means that newer students relying on personal savings may find their home currency no

longer goes as far in the US as it once did.

This currency shift means that American institutions and policymakers will need to monitor their

market closer than ever before. There is a strong opportunity for the sector to grow its

reputation for supporting students through these tough financial times by offering scholarships.

At the same time, competing destination markets like Australia and Canada could leverage the

strong USD to appeal to students who find their budgets suddenly unable to accommodate the

shifting currency value. Likewise, with the euro falling below parity with the USD and the

British pound potentially not far behind,25 the EU and UK may be more affordable destinations

than before. As the only Anglophone country remaining in the EU, Ireland seems likely to be a

major beneficiary.

For more on how the rise of the American dollar will impact

global student mobility, read the Uniwolc data blog, ApplyInsights.

Post-Graduation Work Opportunities an All-Important Driver

Post-graduation work opportunities remain a key consideration for students choosing between

destination markets. As mentioned above, 80% of our recruitment partner network indicated that

post-graduation work opportunities are a top consideration for their students. Other surveys

have found that nearly half of all students intend to stay in their destination market to work

after graduation.26

With post-graduation work opportunities of such paramount importance to students, the generosity

of these programs offers a key opening for destination markets to get a leg up on the

competition.

Canada’s Post-Graduation Work Permit Program (PGWPP) allows international graduates to stay and

work in Canada for eight months to three years, depending on the length of their study program.

The PGWPP is particularly highly regarded.27 When surveyed, 97% of Uniwolc recruitment partners

agreed that Canada provides strong post-graduation work opportunities for their students.

The program’s sky-high approval rate may be a factor. More than 97% of eligible PGWPP applicants

were approved between January of 2016 and July of 2022.

Please rate your level of agreement with the following statement:

This country provides strong post-graduation work opportunities for my students.

In Australia, the Post-Study Work stream allows international students who’ve recently graduated

with a degree from an Australian institution to live, work, and study in Australia for two to

four years, depending on their qualification.28 However, the Australian government announced in

September that graduates in select sectors will be eligible to stay and work for an extra two

years.29 This change makes Australia’s post-graduation work program the most generous among the

four main English-language destination markets, and may well push Australia ahead of its

competitors when it comes to attracting international talent.

The introduction of the Graduate Route (GR) in the UK helped propel international student

enrollment growth by 8% in 2020/21.30 Incredibly, this helped the UK reach its 2030 goal for

international student enrollment nine years ahead of schedule. And there’s room for even further

growth: in student surveying, nearly 60% of prospective students said they would be more likely

to consider studying in the UK if international students could remain in the country for three

years instead of two.31

The US trails other markets with respect to post-study work rights. The Optional Practical

Training (OPT) program extends for just one year for most students, with science, technology,

engineering, and mathematics (STEM) students eligible for a two-year extension. Beyond this, the

transition from OPT to a permanent residency pathway is a particularly difficult one.

Nevertheless, OPT is well subscribed, with more than 200,000 international graduates working

under the program in the 2021 academic year.32 In January, the Biden administration took steps

to make OPT more accessible to international students by making 22 additional STEM sub-fields

eligible for the two-year OPT extension.33

When I was considering which country to study in, the countries

where I had a path to staying long-term after graduation were the ones I found most

attractive.

— Joseph, Nigerian International Student

Destination Markets Alleviating Work Barriers for International Students

The expansion of post-graduation work opportunities is exciting to see. But new and current

students often need to work part-time to pay for their tuition and living expenses. How

destination markets support these efforts is another key area of differentiation.

The Canadian government recently lifted the 20-hour weekly limit for international students

authorized to work off-campus.34 There are more than half a million international students in

Canada, and this change will not only help increase their weekly income and alleviate cost of

living pressures, but also increase their work experience and possibly help prepare them for

later career success.35

These policy changes are sure to be welcome news for students,

their parents, and employers across Canada, making it an important improvement that will

keep Canada top of mind for international students and competitive as a nation looking to

attract top talent.

— Meti Basiri, Co-Founder and CMO, Uniwolc

Like Canada, Australia has temporarily relaxed the working hours cap for student visa holders.

But this relaxation will end on June 30, 2023.36 This means that working hours will once again

be capped for students following this date. In the UK, international students are capped at 20

hours of work per week during the school term.37 The US also caps working hours for

international students at 20 hours per week.38 Although Canada’s relaxation of its working hours

cap is scheduled to end on December 31, 2023, these changes should boost the country’s

reputation as accommodating to student needs, thereby giving the country a competitive

recruitment edge over other destination markets over the next year.

Global Need for Workers Driving Competition for International Students

If destination markets are expanding post-graduation work opportunities, does that mean

international students are well positioned to fill gaps in the job market? Job vacancies reached

record levels while unemployment rates fell to multi-decade lows nearly across the board in

2022.39 This means that organizations experienced a growing need for workers, but faced a

shrinking pool of available talent to hire. While this trend will likely shift in 2023 due to

the looming recession, for many high-skill positions, student recruitment should remain a vital

component in filling those roles.

This is perhaps most evident in the healthcare industry. Tragically, the World Health

Organization (WHO) estimated that between 80,000 and 180,000 health and care workers lost their

lives due to COVID-19 between January 2020 and May 2021, a figure that has likely risen in the

year and a half since.40 Other healthcare workers have sought out new sectors for employment.

These losses have contributed to a global crisis in which nations face a shortage of healthcare

workers.41 Recruiting professionals from one country to another will not solve this

crisis—instead, new workers need to be trained.

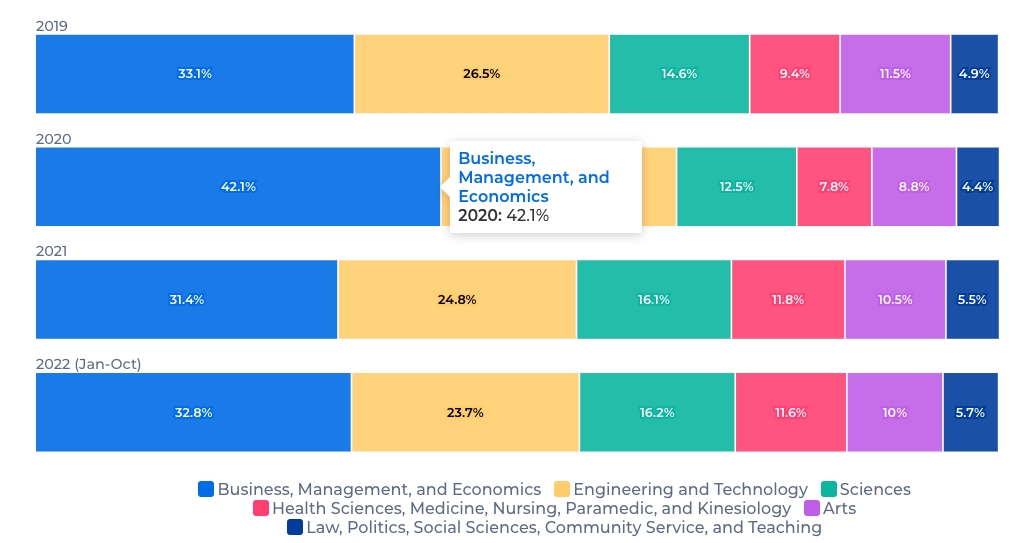

Encouragingly, this need may be starting to reach the ears of prospective students. Searches for

fields related to the health industry on the Uniwolc Platform jumped 3.8 percentage points in

2022 compared to 2020. Searches for science programs rose by 3.7 percentage points over the same

period. But business programs still account for nearly one-third of searches, and further

incentives may be needed to get international students into high-need careers. The time may be

ripe for other governments to follow the US in offering extended post-graduation work rights for

STEM students.

The Shifting Face of International Education

Whether or not international students hold the key to solving the labour shortage across

destination markets, many will leave their home country to live, work, and study far

away. With this in mind, it’s important to take a closer look at student mobility not

just from the perspective of destination markets, but from source markets as well.

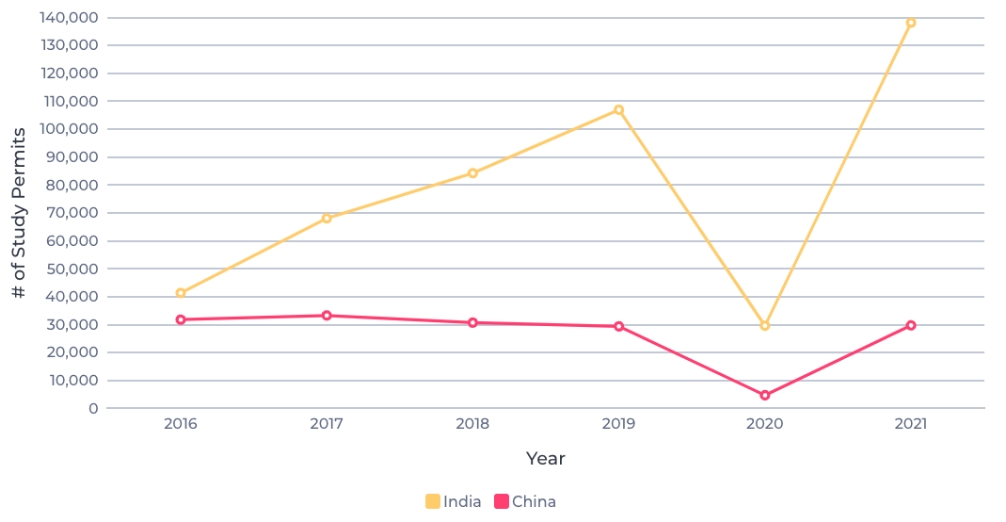

Any conversation about source markets begins with China and India. While emerging markets

will be critical means of diversifying student inflows moving forward, by virtue of

their sheer size, China and India will continue to dominate as the top two sources for

international students.

That said, the two markets are headed in opposite directions. China’s population of young

adults (aged 18 to 23) declined by nearly 50 million between 2010 and 2020, and it’s

expected to shrink by another 35 million by 2050.42 At the same time, the Chinese

government is actively working to develop their post-secondary education systems and

institutions, transitioning China from a top source market to a destination market of

its own.

India, on the other hand, has become home to the largest population of young adults

worldwide, with more than 150 million in 2020. Though the Indian young adult demographic

is expected to decline somewhat over the next 30 years, India is still projected to

become the world’s largest middle class consumer market by 2030.43 And near-term

economic projections for India are more favourable than those for China, as well as the

Eurozone and Latin America.

The rise of the middle class in India will enable more Indian students to consider

studying abroad, and this massive population of students seeking to further their

education will drive recruitment conversations for years to come.

These shifts are already having an impact on student inflows to top English-language

destination markets. Indian student inflows to Canada surpassed Chinese student inflows

in the mid-2010s, and as of December 31, 2021, there were more than twice as many Indian

holders of Canadian study permits as there were Chinese holders.

In contrast, the news that more Indian students than Chinese students were granted UK

sponsored study visas between July 2021 and June 2022 surpassed the expectations of most

across the sector. And indeed, the rate at which the gap between the two countries

closed is remarkable. As recently as 2019, China sent 80,000 more students to the UK

than India. While the total number of Chinese students in the UK still greatly outpaces

the number of Indian students, the gap is narrowing.44

A similar phenomenon has taken place in the United States. The US Department of State

issued more F-1 student visas to Indian nationals than Chinese nationals in the 2020

fiscal year, and while China surpassed India again in 2021, the margin was less than

10,000 students. In 2019, the gap was more than 60,000 students; in 2015, it was nearly

200,000. Like the UK, the total number of Chinese students in the US remains well ahead

of the total number of Indian students, but the divide is shrinking.45

The number of Australian student visas granted to Indian nationals surpassed 37,000 in

the 2018-19 Australian government fiscal year, more than double the total in 2015-16.46

At the same time, the number of student visas granted to Chinese nationals declined to

just under 52,000, the first year-over-year drop since 2011-12. But Indian student

inflows to Australia fell more sharply than Chinese inflows during the pandemic, bucking

a trend seen elsewhere around the world. Last year, more than twice as many Chinese

nationals were granted an Australian student visa as Indians.

New Canadian Study Permits Issued, China vs. India, 2016-2021

It’s important to note that the more recent decline in Chinese students going abroad matches a

larger pattern across the rest of East Asia. Fewer students from the region have gone abroad to

study since the onset of the pandemic, perhaps due to stricter lockdown measures or more

uncertainty about travelling. But while we may be in line for a small bump in Chinese student

outflows as COVID-19 fades even further into the rear view mirror, expect the underlying

demographic trends to eventually prevail—and the competition for students to grow even more

intense.

What does the international education ecosystem look like with India at the top? Chinese students

have repeatedly emphasized institution ranking and reputation as key drivers when choosing where

to study. For Indian students, graduate outcomes are paramount.47 Expect post-graduation work

opportunities and career success metrics like graduate employment rate to become even more

salient in the sector as Indian students dominate.

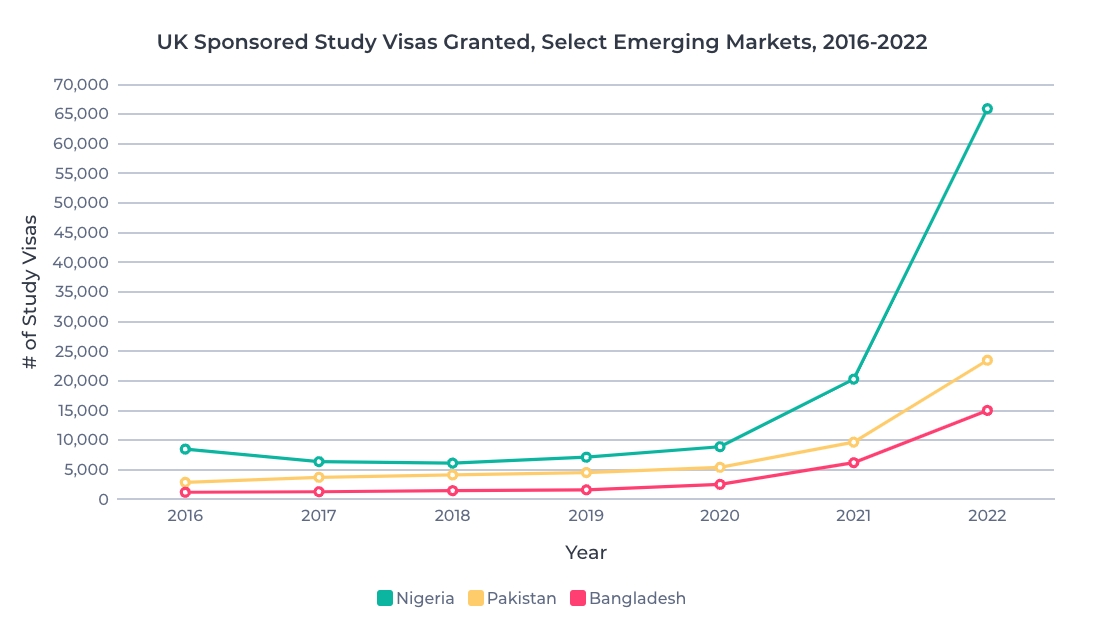

Key Markets Emerging in Earnest

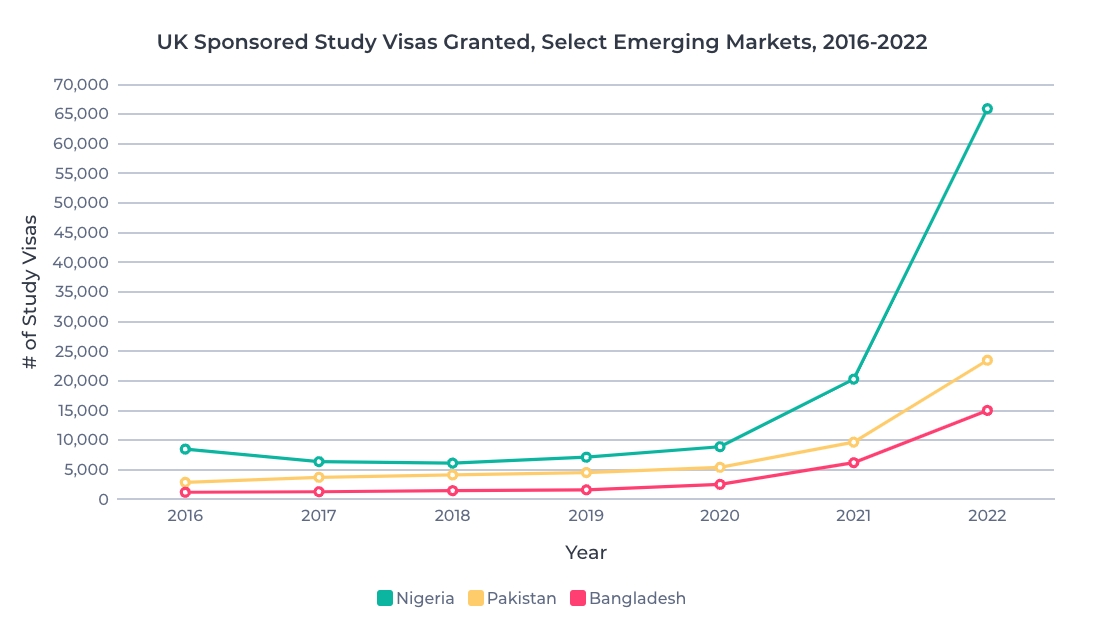

In last year’s trends report,48 we identified six high-growth-potential markets that we felt were

ready to expand and that remained relatively untapped by institutions in each destination

market. Those markets were Nigeria, Kenya, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, and Indonesia. While our

forecasts were (and remain) intended to be long term, we feel it’s worth briefly reviewing the

performance of some of these markets to see how their international student populations have

shifted over the past year.

International education stakeholders have long touted

Nigeria as the next major source market for international students, and for

good reason. The demographics are extraordinarily favourable. The population

of Nigerians aged 18 to 23 is expected to surpass 30 million by 2030. At the

same time, Nigeria’s GDP per capita is predicted to grow by 30%.49

With a post-secondary student population poised to

surpass that of the US by 2025 and an education system unlikely to be able

to accommodate the increasing demand,50 Pakistan is a particularly

attractive source market for institutions across the globe.

Bangladesh made headlines, particularly in Indian media,

when it surpassed its neighbour to the west in estimated GDP per capita in

2021.51 Though Bangladesh has faced significant economic headwinds over the

past year, its outlook remains solid.52 Over 50 million more Bangladeshis

are expected to join the middle class by 2030. And with Bangladesh’s

domestic education system unable to accommodate this influx of

post-secondary students,53 more and more Bangladeshis are primed to look

abroad to study.

We remain excited about Nigeria, Pakistan, and Bangladesh as high-growth markets. While the UK is

the clear leader in all three markets at present, institutions in other destination markets

would be well served to direct recruitment efforts to these countries with growing young adult

populations, developing economies, and overtaxed domestic education systems.

The Long View

So far in this report, we’ve focused on key trends we see impacting international education right

now, and how governments and institutions can respond to shifting student preferences in order

to ensure they can remain competitive in an increasingly challenging landscape. But some of the

most profound shifts happening in our sector will play out over years, if not decades.

In this section of the report, we look at a pair of trends we see as having a longer horizon. We

begin with technological innovations we see taking hold in the medium term.

Momentum for Online Delivery Stalled, but Hybrid Viable

While online programs were gaining momentum prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 and 2021 saw an

explosion in digital course offerings. With international students unable or unwilling to

travel, governments demonstrated flexibility by allowing students to begin their international

education from their home country while remaining eligible for post-graduation work rights.

With pandemic restrictions waning, students have made a welcome return to the physical classroom.

In a June 2022 Institute of International Education survey, 89% of US institutions reported that

the majority of their international students were once again studying on campus.55

What does that mean for the future of online learning in international education? Quacarelli

Symonds (QS) student surveying in early 2022 found that across markets, just 1 in 5 students

were considerably interested in online or distance learning.56 This was broadly consistent with

previous findings, suggesting that the pandemic failed to expand the long-term viability of the

purely virtual learning model. When asked to explain why they weren’t keen on online delivery,

students pointed to a lack of access to university facilities, wanting to meet other students,

and wanting to live overseas while studying.

There remains considerably more interest in a hybrid or blended learning approach, which combines

in-person instruction and online delivery. 65% of candidates surveyed by QS indicated that they

would find this approach either somewhat or very appealing, citing the convenience of studying

from any location and the advantage of being able to study while working.

If hybrid delivery is to gain a real foothold post-pandemic, we believe it will be through

students’ wallets. With the lifting of weekly work hour caps across select destination markets,

students may elect to pursue additional time on the job—particularly as affordability concerns

mount. Institutions could alleviate those financial concerns further by lowering tuition rates

for online or hybrid programs, which many international students have reported would make them

reconsider online studies.

New Competition from Non-Anglophone Destination Markets

When it comes to recruiting students, the US, the UK, Canada, and Australia will face growing

competition from destination markets outside the English-speaking world in the coming years.

International students began returning to China this fall after being shut out of the country for

more than two years due to COVID-19 border restrictions. However, China’s zero-COVID policy,

which has included harsh lockdowns and disruptive repeat-testing policies, remains in place.57

China hosted almost 500,000 international students as recently as 2019, and while its ongoing

restrictions may make for a slower recovery than countries such as Australia, we expect a full

rebound in the coming years.

Russia enacted a strong international student recruitment plan over the past five years. From

2016 to 2021, the number of international students in Russia grew from under 300,000 to nearly

400,000.58 Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 severely destabilized the sector, however,

with safety concerns paramount and sanctions limiting students’ ability to access funds from

back home.59 Volatility in Russia may open up recruitment opportunities for the big

English-language destination markets in Eastern Europe and Central Asia if institutions are

willing to invest in those regions.

A record 350,000 international students were registered at German universities in Winter

2021/22.60 This marked an 8% increase from the previous year. Germany’s greatest competitive

advantage is its free tuition for all students, but there are signs this perk could vanish.

Earlier this year, the state government of Bavaria granted public universities the right to

charge fees to non-EU international students, but complexities implementing the new rules have

preserved the status quo for now.61

Other, smaller destination markets that have seen significant international student growth over

the past 5 to 10 years and which have shrinking or stable domestic student populations62 include

Italy, Spain, Japan, and the Netherlands. The development of these markets will increase

competition for international students worldwide, even as new emerging markets provide larger

student populations.

Stay Tuned

In this report, we’ve touched on a wide range of factors that have driven international

education trends post-pandemic and which will influence the sector in the years to come.

But this report is not meant to be exhaustive. Many of the trends we’ve discussed are

more complex than we’ve outlined here. Others which we’ve barely scratched the surface

on may prove more influential than anyone predicted.

In this era of increasing student choice in international education, one thing is

absolutely certain: With unemployment rates at historic lows and job vacancy rates at

historic highs, success in attracting the best and brightest international students

means more success in the larger global competitive sphere.

More than anything else, the countries and institutions that succeed in bringing in top

talent will be those that prioritize student success. Look for governments to continue

to craft policies that facilitate student mobility, whether by investing in more staff

to alleviate visa processing slowdowns, or by offering more generous post-graduation

work opportunities. And look for institutions to revisit their international recruitment

strategies to gain a global edge, including by strengthening ties to industry and by

pursuing more flexible learning models.

As for Uniwolc, we’ll continue to provide key data insights and forecasts across markets.

Over the coming weeks and months, we’ll be releasing detailed articles and analyses that

expand on some of the topics we discussed in this report.